4 Cost Savings Tips for Ecommerce Supply Chains

The continual reduction of costs in the supply chain is a top priority for supply chain managers. The trick is think of it less as a cost cutting exercise and more as a strategic job: the funds being saved should propel differentiation, like free shipping or loyalty programs, which in turn open up new cost cutting opportunities.

Well, normally that’s the case. Since we are in a pandemic, simply having more cash on hand is critical for most companies too. No one wants to make layoffs, and COGS likely aren’t going down, so trimming costs along the supply chain is the next high-impact bucket.

What follows are 4 cost-cutting ideas that might work for different companies in different situations. They are based from my experience at Amazon during past crises, or from what peers much smarter than me have shared.

Cost Savings Tip #1: Renegotiate Carrier Contracts

Everyone is hurting right now, including logistics behemoths like UPS, FedEx, USPS, and DHL. They need the volume.

Right now is the time to go back to the contract, and ask about renegotiating to find better terms.

Your leverage will depend on which of these three brackets fit you over the next 6 months:

- Increase in sales: “It’s Christmas without the planning,” a friend at a necessities-based ecommerce retailer told me. Their volume is through the roof. If you are an ecommerce business and are experiencing a situational uptick in sales, you are in a great position to renegotiate your carrier contracts because you can provide the volume of shipments that they are seeking.

- No change in sales: Some ecommerce companies are seeing no change, like those in entertainment categories for example. You are still in a strong position to renegotiate because you can provide consistent shipment volume.

- Decrease in sales: Some categories are taking a hit in which cutting costs is of particular urgency. Even with decreased volume, you still have an opportunity to renegotiate with carriers for a few reasons: (1) Not all companies are going to spend the time to renegotiate right now, so beat them to the punch; (2) All of UPS, FedEx, and USPS are hurting, so pitting them against each other to compete for your volume, even if decreased, will drive the outcomes you want.

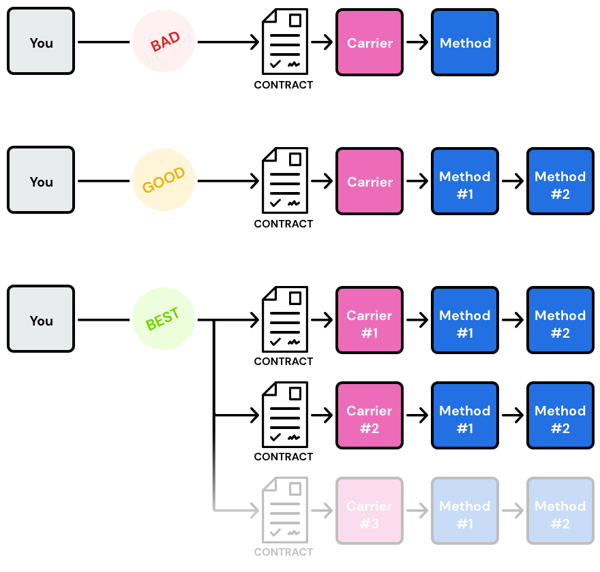

My biggest piece of advice with carriers is to understand that there is no unilateral “best rate” to be found. No carrier has the best rate for all situations.

Consequently, we typically advise holding contracts with multiple carriers so you can make use of algorithmic decision making to always pick the cheapest and fastest option. It’s even more beneficial to consider that right now. All carriers are starving for volume, which gives you a little more leverage today than you might have had yesterday in securing cheaper rate tables.

So, the main tip: Explore adding multiple carrier contracts in addition to renegotiating with your existing carrier if you only have one on hand.

Here are some additional considerations:

- There will always be a trade off between speed and cost, and the trade off dynamically shifts back and forth over time as market conditions change. A few months ago, speed mattered more than cost: 50% of online shoppers preferred 2-day shipping when making a purchase. Now, given a pandemic, consumers are much more reasonable. So much, in fact, that even Amazon has been adjusting delivery expectations. Therefore, with preserving cash the most important thing right now, it is wise to optimize towards slightly longer delivery times (think 3, 5, or at most 7 days) in order to realize major cost savings. Keep in mind that at some point in 2020, the opposite will be true: the pendulum will flip back towards consumers preferring speed, so you must be ready with a carrier contract and supply chain design that supports 2-3 day shipping, too.

- Last-mile delivery companies might be an advantageous partner to add into the mix.

- Assuming you can cut a better deal, the best length of the contract is dependent upon whether you think you will be in a better position or they will be in a better position X months from now. Right now, shorter contracts are likely your friend. Shoot for a 6-month contract so you can renegotiate from an even stronger potential position if and when the economy turns back around.

- Quick note: Contracts are normally reviewed annually. Considering how quickly things are changing it might make sense to put guidelines around conditions that would justify reviewing the contract sooner (e.g. a condition that gives you the option to review 6 months from now).

Cost Savings Tip #2: Increase Your Inbound Cost-Per-Unit

A lot of factors go into placing a purchase order. The biggest factors include forecasted demand, vendor lead time, and order frequency. These factors all get mixed together into a probabilistic soup to produce an order quantity. This process can be automated or manual, but the calculation must ultimately consider how much you can control all of these factors when arriving at an order quantity.

Based on what you can and can’t control, here is a tip that is counter-intuitive: You will actually save more money by increasing your inbound cost-per-unit.

Let’s breakdown what that means by digging into these factors with a little more detail:

- Forecasted Demand is a prediction of what customers will purchase in a future time period. During a time of uncertainty this input is very difficult to predict.

- Vendor Lead Time is a prediction of how long it will take your supplier to deliver your goods. This is also unpredictable because the upstream supply chain is a mess as a result of the pandemic.

- Order Frequency is how often you are cutting purchase orders. When you increase the frequency of ordering, you order for a smaller period of demand because the next order comes in less time. Unlike the other two factors, order frequency is something that you have complete control over and is very predictable.

Like most logistics puzzles, you benefit most by putting energy into what you can control. Given the reality of the world right now it is very unlikely that demand or lead time will be predictable. That is why right now is the perfect time to look at increasing your order frequency to give yourself more opportunities to change your decision.

A simple example of adjusting order frequency

The best way to explain is with a simple example. You will have other complexities, but let’s keep it simple to illustrate the basic principles.

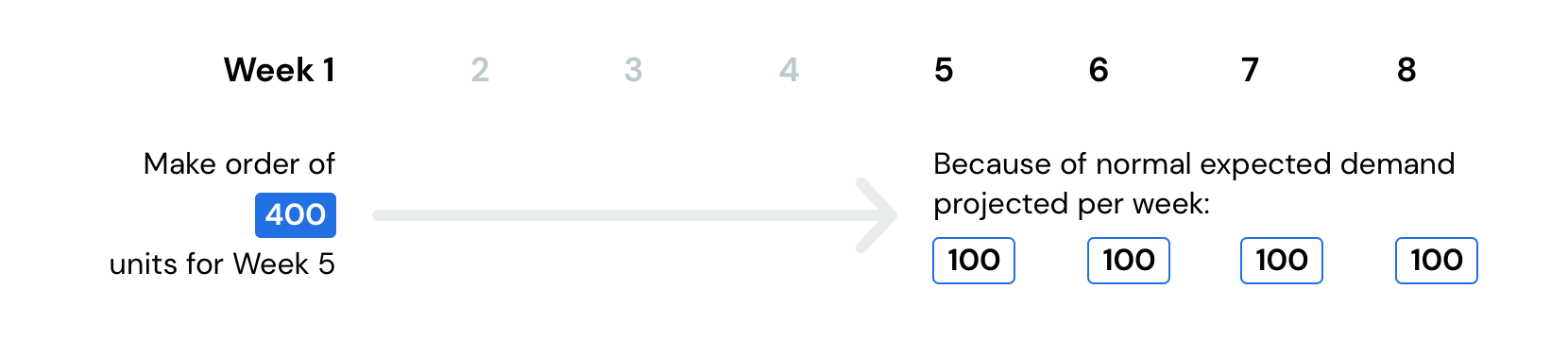

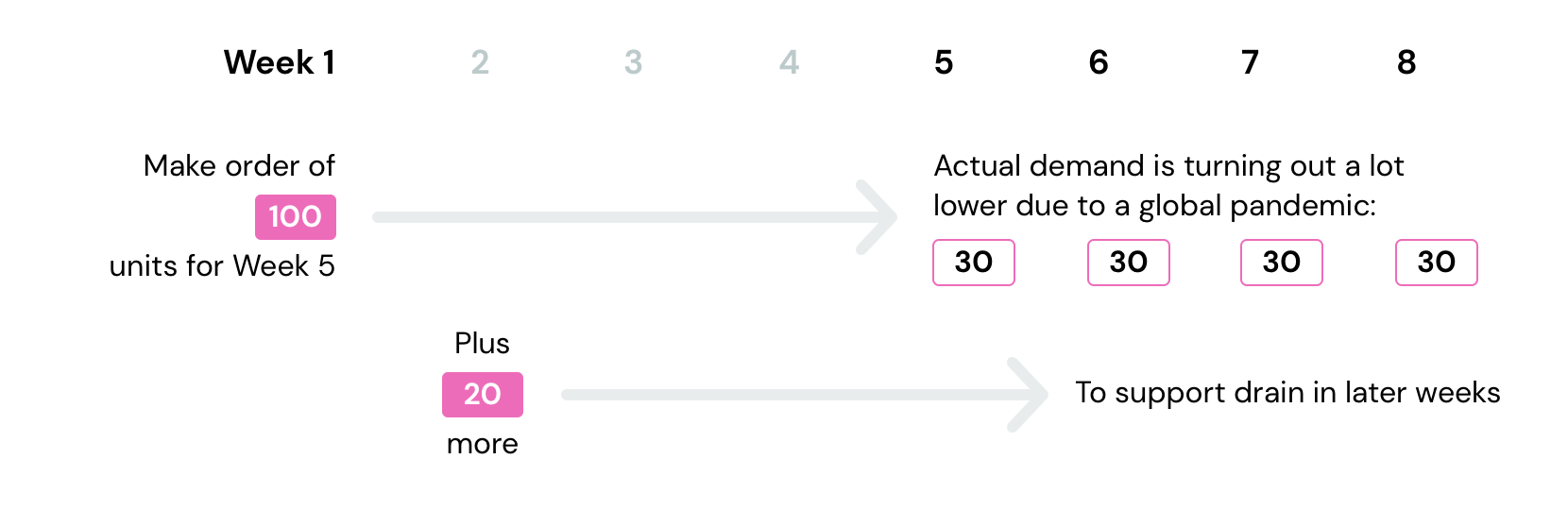

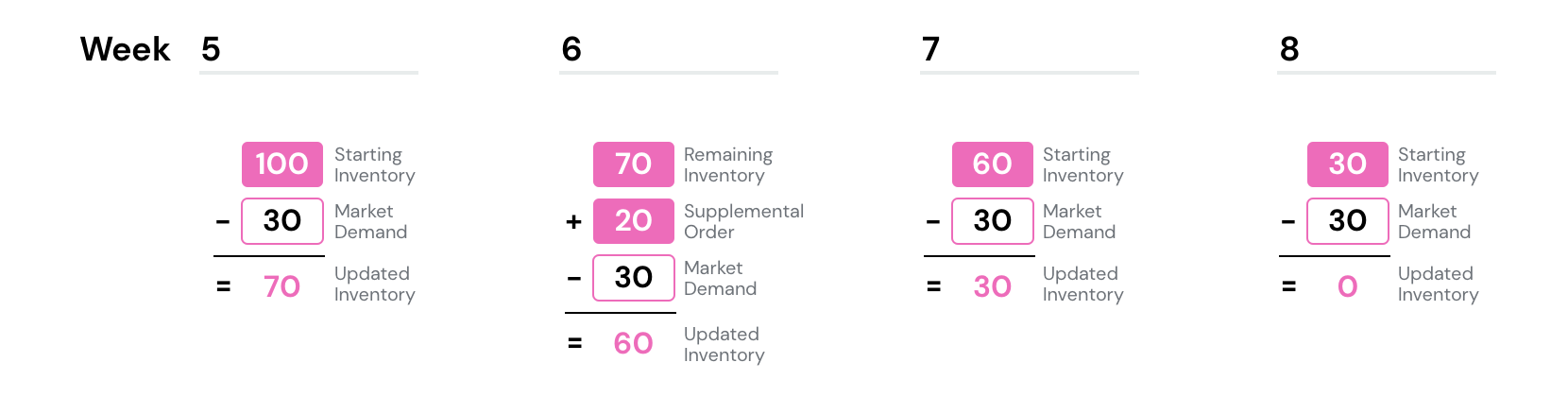

For this example I’m going to assume you are doing a normal best practice of monthly procurement to get a volume discount and lower cost-per-unit on shipping. The order is based on a normal projected demand of 100 units per week for this hot product. The vendor lead time is typically four weeks.

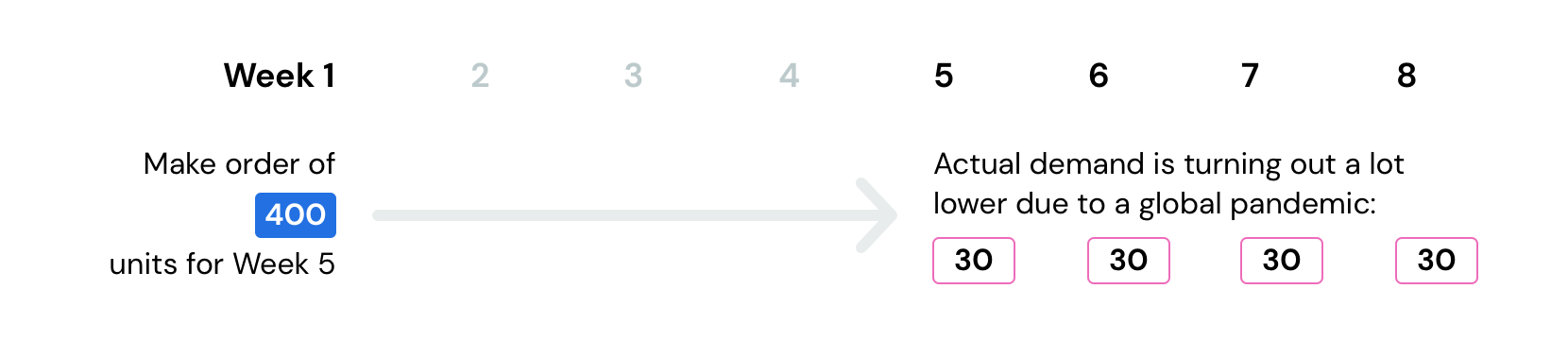

Except it turns out that demand has really dropped because of the global pandemic. There is uncertainty everywhere. A couple days after the order is placed it becomes clear that you are no longer going to sell 100 units a week but you have already placed the order and 400 are on the way.

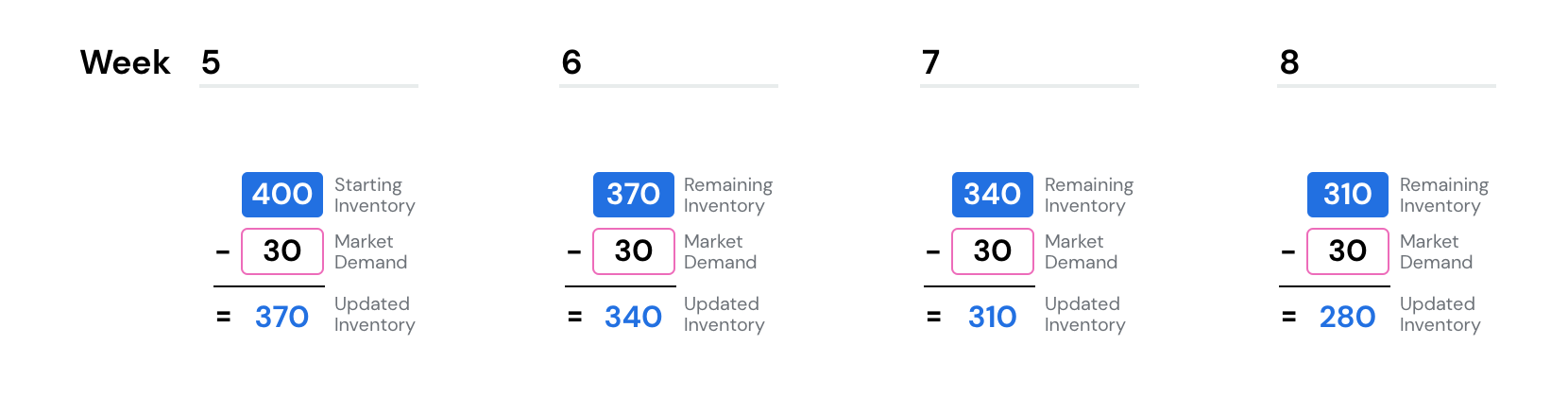

Now you will exit next month with 280 extra units of inventory. The type of inventory will determine the severity of the miss (bananas vs. batteries, for example). From a modeling point of view, however, the excess inventory added risk to the business because you tied up cash in assets that aren’t usable. Right now cash is more valuable than inventory.

Focus on what you can control

Instead, think about de-prioritizing volume discounts and increasing order frequency to something closer to a weekly cadence.

Let's look at what would have happened in this scenario if you were on a weekly order cycle.

In this scenario you would have ordered only 100 units to cover Week 5 in your first order because you know that you will get a chance to order more next week for Week 6. Just like above, you place your order for 100 units and then immediately realize that demand is dropping. You order 20 additional units in Week 2 instead of 100. Forecast continues to drop so in Week 3 and 4 you don’t place an order at all.

When the demand is uncertain like it is right now it is important to focus on levers that you can pull to give you additional flexibility, in particular the levers that help improve your cash position. The price breaks from placing monthly orders will land a huge amount of overstock. The smaller cost-per-unit amount wasn’t worth the cash flow problems you created.

While reducing the size of the orders will increase your inbound cost-per-unit, it gives you the flexibility to adjust to demand fluctuations which is a great way to improve your cash position.

Cost Savings Tip #3: How Opportunistic Economic Orders Can Boost Your Cash Position

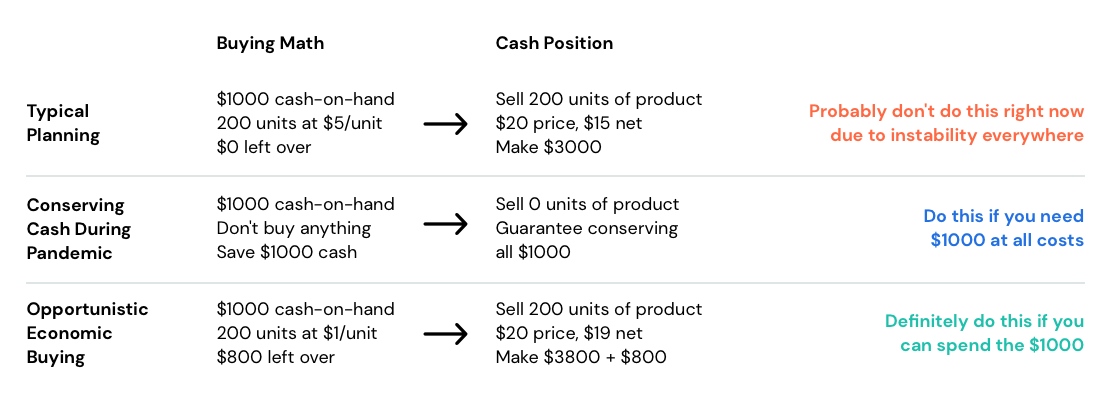

Here is another counter-intuitive move that might eat into immediate cash reserves, but produce stronger cash flow in a short amount of time with a fast turn around, thus strengthening your mid-term balance sheet if you have the cash available today to do so.

The topic is economic ordering.

How much do you buy?

Economic ordering is a larger topic but it’s worth diving into because of the rapidly changing economics of the world today due to the pandemic.

At a high level, economic ordering is deciding how much inventory to buy based on maximizing economic outcomes like profit or revenue. The calculus involves all factors that affect the profitability of the transaction: COGS, fulfillment cost, the sale price, whether it gets marked down, etc. The actual calculus depends on the specifics of your business.

There are generally two main approaches to buying economics.

The first is a budget-based approach where the total spend for a buying cycle is managed through a top-down buying process. It is what traditional S&OP does. Basically, demand forecasting informs budget scope which informs what to buy. This works well in situations where demand across SKUs is predictable because shoppers are predictable. For example, if a customer buys a winter coat from your site they will likely not buy another winter coat this season.

The second approach is a bottoms-up approach that looks at each SKU independently and decides how much inventory to buy based on the specific demand and profitability of that SKU. This is mostly what we did at Amazon because each SKU was relatively independent. For example, just because a customer bought a Nespresso does not mean the consumer will buy coffee cups too. Bottoms-up is usually an independent exercise for every SKU, but in reality cash flow and warehouse space constraints often override the pureness of the exercise. I want to focus on the bottoms-up approach for this discussion.

Top-down is easier to isolate demand stability per customer profile, while bottoms-up is easier to isolate demand stability per SKU.

Bottoms-up ordering when conditions are stable is interesting because, if all factors are stable, the actual calculation is not very interesting at all. Imagine the scenario where I have stable customer demand and the purchase price for the item is locked into an agreement with a vendor who won’t go out of business. The math ends up being straightforward because the purchase timing isn’t changing (no advantage to buying early) and if I buy too much I’ll just sell it next week (no risk of markdown).

But things are not so stable right now.

Buy Low, Sell High

The first obvious observation about the current state of the world's ecommerce supply chain is where demand is outstripping supply. Goods that fight COVID-19 are the strongest example as hand sanitizer and face masks are out of stock everywhere. There are lots of categories where this is the case (hair grooming products!), and the knock-on effects up the supply chain into manufacturers and suppliers will reverberate into your supply chain too.

The second observation is that this has introduced an immediate opportunity for price gouging because of our old friend scarcity pricing. Similar price inflation can float up the supply chain and is one way to feel the reverberations.

It turns out that the converse is also true but we don’t pay as much attention to it because it doesn’t represent an immediate business problem like price gouging from a supplier. Specifically, demand patterns have changed enough with goods where demand is not outstripping supply that there is excess inventory in all stages of the e-commerce supply chain. Anytime this happens, some portion of manufacturers and suppliers will want to offload their excess supply now to increase their cash flow.

It goes without saying that right now is probably an excellent time to look for discounted inventory if you have the cash. Heavy discounts on product cost will almost always outweigh holding cost even if it is for several months.

The conundrum is whether to spend the cash now or not.

How playing offense factors into improving your cash position depends on turnaround time related to the economic purchase. If your business has fast turnaround times, then you will see the profit gains quickly, with the extra profit hitting the balance sheet fast enough to strengthen your cash position in a way that didn’t create much risk for your business. If you have very long turnaround times from when you would make an economic purchase, then you might want to consider whether or not spending the cash now on opportunistic discounts is worth it.

Buy High, Sell Low?

If you are one of those manufacturers, suppliers, or retailers who has excess inventory, I also caution you to be careful about marking down inventory too quickly.

Using the same principle as above, the cost of holding inventory for a couple extra months is going to be small in comparison to heavily marking the item down now to sell it.

Businesses always have strain because of cash flow but if you can weather the storm you will be in a much better position when things clear up.

If possible, look for other angles to boost cash reserves first, and think of liquidating excess inventory as one of the last resorts.

Cost Savings Tip #4: How to Deal with Overstocks

This is a situation many will likely face in summer due to the bullwhip affect, which is different than the situations you faced at the beginning of the pandemic in March.

Consumer predictability has been erratic at best, so short-term forecasting has been difficult. A surge in demand for a certain product has or will quickly dissipated for many companies.

The result is "overstock" — a frustrating scenario for supply chain managers.

There are ways to handle overstocks to generate either quick or sustainable cash flows. The methods come with a caveat however. They aren't a universal solution, but potential tools to use if

- Your company is stuck in a situation with large amounts of overstock due to erratic customer demand, and

- You have the urgent need for cash or desire to reduce future costs to increase margin.

What to do if you want to reduce the costs of overstock

Let's establish a few assumptions so you can determine if your company and situation is a fit.

→ Let's assume you believe the overstock will still have some demand, just on a longer time horizon. It's not dead stock.

→ Let's assume you are comfortable tolerating the stowage costs, and desire to sell the stock at full price. No discounting.

→ And let's assume you have more than one FC.

If this is the case, then reallocation of overstock based on geographical projections will save you major basis points in margin.

Reallocation is often a tough pill to swallow, though, because of the upfront costs to ship a truckload cross-country. It's an underutilized tactic.

The key insight stems from the fact that outbound shipping from FC to final destination is one of the most expensive operational expenses. It can be as high as 70% of total logistics COGS, depending on the makeup of your business.

Subsequently, saving a big chunk of 70% shipment-over-shipment more than makes up the difference of the painful decision to pay to send an FTL shipment between FCs.

A simple model:

- On average, an LTL shipment from New Jersey to Reno is $2000, to use a round number. Your (literal) mileage may vary!

- Hitting West Coast zones from Reno saves on average $5 from outbound shipping costs.

- Therefore, all it takes is 400 SKUs to make back your money. It scales in both directions, too.

In this specific pandemic overstock scenario, you should consider that you are potentially overstocked at the FC level and not in a macro sense. Meaning, eventually the stock will sell, but maybe it's selling better in west zones than east zones, so your east FC is constantly sending long-haul shipments to customers. That's what we call a margin eater!

Instead, look at historical purchasing patterns and make an educated projection on future sales of the remaining overstock. You might find reallocation to be a strong way to improve cash flow as the overstock slowly sells.

What to do with overstock if its dead

Some companies might be facing the prospects that they overestimated demand and the way the pandemic has played out has resulted in severe overstock of something they feel might not ever sell.

That's a tough situation to be in.

In this scenario, the calculus comes down to two measurements:

(A) Either you take the hit by paying for a warehouse expansion to stow the goods in hopes of eventual sale.

(B) Or you take the hit in margin by liquidating the goods via resellers.

I'm normally a proponent for ecommerce companies to consider liquidation as a last-resort idea. Most of the time the math works out to hold onto stock and eventually sell it at full price (or at least not pennies on the dollar).

But these aren't normal times.

In this case, ecommerce liquidators are a boon for a few reasons:

- Online discount sites have a much larger reach than physical resellers (outlet malls, etc.). Your goods will be found, making the effort worthwhile.

- Because it's ecommerce, the margin hit is different than physical discounters. It's not quite as bad, making the math better.

- While CX is still proving to be important, it is a pandemic, and more people are price sensitive than usual, so you might get your brand into the hands of someone who might not have tried it otherwise because of a sale. This could have positive long-term customer retention effects.

- And, the most irregular of all, you probably need cash! The pandemic has put a strain on balance sheets. So even though the margin hit hurts, getting the cash in hand for *overstocks* is better than paying yet more cash to expand a warehouse.

If you want to talk about this topic or any other, feel free to message me on LinkedIn. Thanks!

Jason is co-founder and CEO of Shipium where he guides the company's vision towards becoming the world’s best supply chain technology platform for ecommerce and retail. Prior to founding Shipium, he spent 19 years at Amazon as VP of Retail Systems and VP of Forecasting & Supply Chain. While there he owned the global software and operations group that powered Prime, Subscribe & Save and Pricing. He is a University of Washington grad and an engineer at heart who loves solving complex scaling problems.